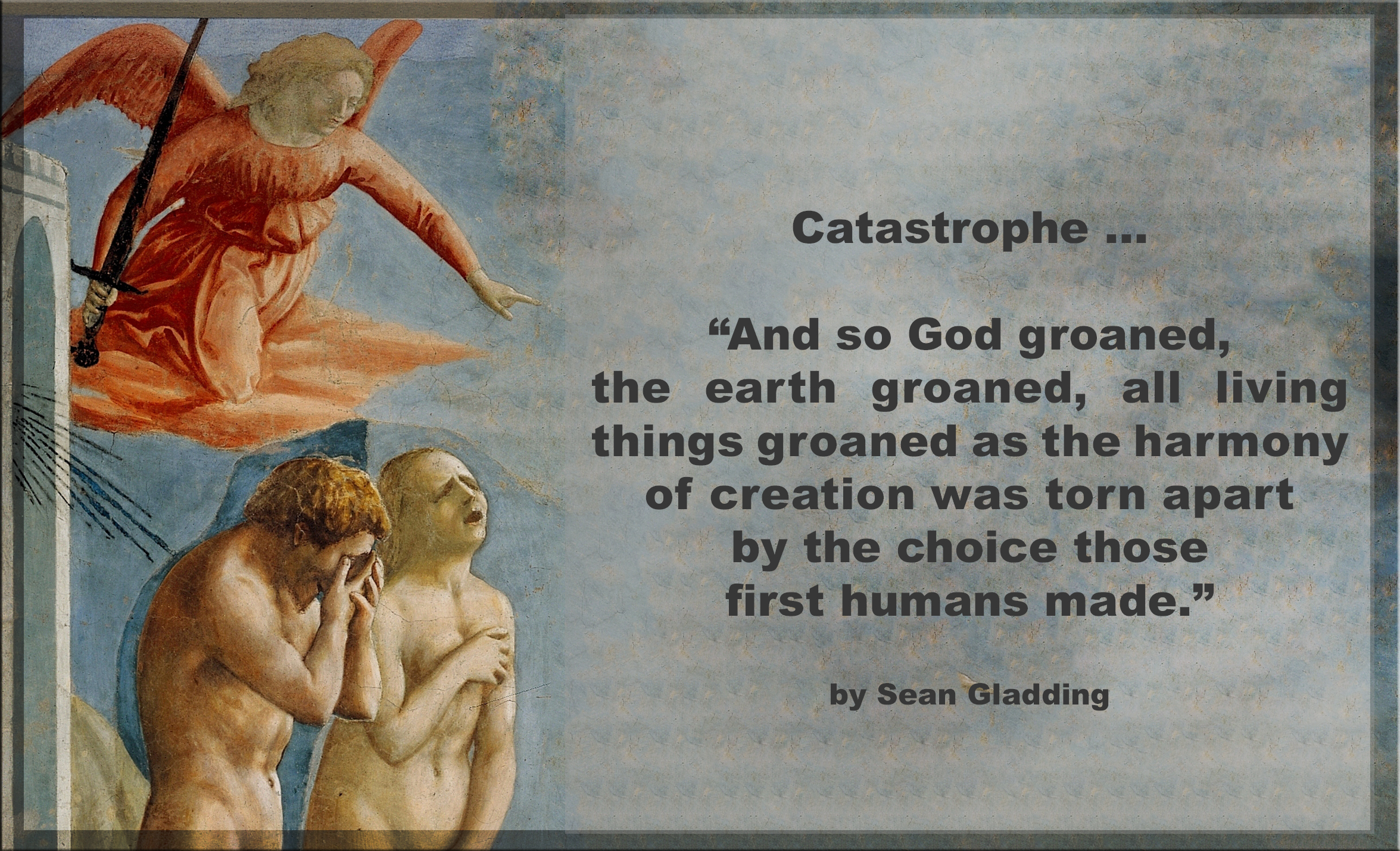

Chapter 2 - Catastrophe

12/02/15 19:53 Filed in: Catastrophe

In chapter 1, we heard of the story of creation and the goodness of God. We left “ha-nahash and ish-sha” (Adam and Eve) in unity in the garden. They experienced the nearness of God and each other, being "naked and unashamed".

In chapter 2, a shadow creeps across this perfect picture as the serpent tempts them to mistrust. As they begin to investigate the fruit of the tree they are not to eat of, a seed of doubt is sown in their minds. Why are they not allowed to eat it? What will happen, really? Surely they won’t die?! The serpent suggests that their eyes will instead be opened and they’ll become like God. Gladding notes that instead of talking to God, they are now talking about God. Their unity is already experiencing a rift as they consider that something other than God could be good. Instead of being a creature, they began to grasp for the power of God.

As they exercised the freedom God had given them, they experienced catastrophe! They did not drop dead on the spot, but something died. They died as one being and were reborn as two, refusing to live in God’s world on God’s terms. Along with Adam and Eve, our exile begins here in life “east of Eden”, as the consequences of their sin impact all of creation.

1) What am I capable of when I believe there isn’t enough?

Bev Patterson: This morning Paul and Verda and I "pondered" this chapter and its legacy of tension and controversy that has been handed down through history. One thing that came up was how shame is so powerful in our lives and how it keeps us in hiding. For me, being "less than," fearing I’m inferior and don’t have what it takes unleashes a deep sense of that shame. What quickly follows is all manner of attitudes, actions, and reactions that have a defensive flavor.

In shame, I am capable of irrational judgement, mean-spiritedness, unhealthy competition, dark-hearted humour, deceit that translates into corrupt action and a desire to undermine my competition. If I were tribal, fully outfitted in the red-meme, I have no doubt I would resort to power-plays that would do physical damage.

But because I live in a more super-ego modality and have been brought up in an atmosphere of deceit when it comes to unsavory tendencies (i.e. anger which remains unconscious), I try to hide these power-plays behind niceties, covert manipulations and an attempt to look good through being dutiful. Outside of covenant with God, these niceties and attempts at being a "good girl" can be just as violent as being part of an ancient tribe who is at war.

These early stories, including the Cain & Abel/Tower of Babel stories are highly cautionary and instructive. They tell us we are still very much capable of murdering our brother/sister, having hubris to the point of competing with the gods and ultimately capable of choosing ego over a deeply loving and honest relationship with our creator. Shame keeps us from being honest and open with God and our human companions, creating a hollow space in us that craves filling.

We have rejected God as our true parent and turn away from the only thing that can fill that hollowness. Instead, we opt for knowledge without wisdom, judgement of reality based on our own instinctual controlling desires, elimination of those that get in the way of our satiation, and an Icarus-like drive that ignores all natural human limitation. Amazing that in light of the stark state of our souls, we, like Adam and Eve, get clothes to keep us warm, a path that offers a way back into relationship with God, each other and creation and a vocation, despite its toil and struggles. This mercy keeps us from becoming completely animal.

Paul Patterson: These Genesis stories are stories of restorative justice. God never blithely lets us off the hook nor does he utterly obliterate us for our disobedience. As Gladding brings to our attention, for every infraction there comes an empowerment, a comfort and invitation to restored fellowship. When we limit the Genesis stories to the literal or historic dimension we miss the narrative lessons contained in them.

What I take from the Adam and Eve story is that mistrust of God’s intentions and the refusal to accept a creaturely partnership with God leads to: scapegoating (i.e., Male/Female, Serpent/Human), deceitfulness, manipulation, shame and self-consciousness. I am called by the text to use these stories as narratives to form my values and virtues. They instruct me that when I mistrust, feel insecure, grasp equality and power then I am living in Adam not in the renewed humanity revealed in Christ the second Adam.

God has first declared his love for me. If I decide based on my own insecurity that God’s pledge of love is untrue and that I need to snatch power and autonomy from God (like Adam or the ancient Prometheus), I am not alive as I should be. I am living in the death-like domain of sinfulness. I constantly have to ask myself where I am getting my God image from... myself or the Shadow/Serpent? Or is it from my God a Creator/Father?

Because I am living this side of the great Catastrophe, my way home comes through attending this pattern, expecting it, working with it and not avoiding it. As Augustine says, the catastrophe is a happy fault (felix culpa) because it brings me to redemption and renewed fellowship, a condition I could never truly realize if I thought I was living a pre-catastrophic life. As shameful as it may feel to admit my creaturely arrogance, it is the only way to dignity and progressive growth, a genuinely free life.

Bev Patterson: Not sure if the question is "where are you" or "where were you"? “Where are you?” seems to carry the tone of concern, without the "wagging finger" whereas "Where were you?” sounds like us when we feel that indignant anger at being stood up and having our egos bruised.

I really liked this part of the chapter — discovering that God is not so much a punitive distant father as a parent who feels the suffering love of losing connection with the creatures he has so thoughtfully brought into being. "Where are you - I miss your company, I miss being in partnership with you, I miss tending creation with you, I miss the conversations that we have as we explore the image that is beginning to take root in you, I miss helping you with my wisdom and me learning what it means to become more human. Where are you - are you ok out there on your own? How is it working out for you? It's dangerous territory out there when you don't travel with love and guidance".

To be asked "where are you" is like God asking Adam and Eve "how goes it with your soul? (It can't be good if you feel you have to cover yourself and lie about the choices and mistakes you've made.)” The question "Where are you" has a discerning, incisive quality to it and it only feels threatening because we have chosen a life of deceit and autonomy. When we accept this question as loving, saving judgement, I think we can run back to God without the shame of question #1 and feel that restorative relief which comes when we are truly known — both in our sin and in our discipleship. "Where are you" in Gladding's perspective, is God waiting for us prodigals to make our way home again.

Paul Patterson: The word that immediately comes to mind as I think about talking about God rather than to God is abstraction. Talking about God is for me to cobble together all the concepts that I have of God and attempt to place what I come up with within my intellectual grasp. Guess who just became God now? Where do I get these ideas anyway? I receive them from my culture, from my autonomous musing. And what do they serve but the advancement, security and flourishing of the same. I put the concept of God at the disposal of my interests. At the lowest conceptualization, I want God to be a fun-loving anarchist whose primary existence is dedicated to my comfort and interests. Within this concept I will always come off as a genuine seeker, a loving character, an authentic human being! I am the hero of my tale and God as the bumper sticker says is my co-pilot.

On the other hand, what if I invite God as he has revealed himself in Christ, scripture and community, into my life? What if I listen to God as he reveals himself, through God’s means of grace, which of course includes saving judgment, what then? Then I live prayerfully. I listen and express myself to the God who accompanies me as if we were alive together in a garden. He walks with me, his Spirit guides me, his Scriptures instruct me. I am open to the ways he consoles me and the ways he sometimes desolates me as needed. I can listen to my conscience, as it is Spirit controlled, and have at least the possibility of submitting or yielding to God’s words.

When I am in this place I am assuming God is actually alive, has an ontology apart from my autonomous constructs and my personal hero narratives. The assumption with this way of life, this way of continuous prayer, is that God is always present, always speaking, always willing to be related to (no matter what mood I am in) . The question then comes, as it did with our early Genesis ancestors, how will I use this freedom to walk with or away from the Creator? Will I conceptualize or will I pray?

Bev Patterson: “Talking about God rather than to God” — good distinction! The theological constructs and principles we create about God will not keep us from our sinful "murderous" ways if we are hell-bent on disobedience. In fact, having a well-crafted tower of ideas can keep us from the harshness of accepting responsibility for our motives and actions. Easier to be sneaky, hide behind intellectualism and play the blame-game if we have reduced God to an idea.

Talking to God, whether it is through "pondering Prayer" or through heart-felt conversation with the body of Christ, keeps us in that relational way which ultimately invites us to be more attentive to our God-given conscience. In relationships that are flesh and blood and when we are rooted in our covenant with the spirit of God/Christ, the stakes are raised as to the kinds of moral decisions we make.

Cal Wiebe: I like how Gladding deals with the Cain and Abel story. He suggests that God wants to give Cain a way out of committing the violence he has planned. God comes to Cain and gives him an encouragement and a warning. Do well and you'll remember you are accepted but beware sin is crouching at your tent flap to have its way with you. When Cain listened to a different voice than God's things got worse.

I think this is a very accurate story of things that actually happen. Last Friday at work, I had an opportunity to see it in operation. I was working up on a scaffold at the end of the day on a very difficult piece of trim. I was tired and impatient and just wanted to finish a frustrating piece of work. I clearly heard once or twice to take a little more time and measure things more accurately but I was fed up and said I'll just make it fit. Well, needless to say, not measuring did not help it fit any better and I left on Friday disappointed with a piece that I had to go back and fix. If I had listened to a saner voice I would have saved myself all sorts of aggravation. I thought of this incident while reading this chapter and realized that God was offering me a way out of frustration but because of my stubbornness I only made things worse for myself.

Connecting this incident to the Story made me realize just how true the story is to our human experience. Made me glad to be studying this book.

Paul Patterson: It shouldn’t surprise us that modern interpreters of the Noah story see in it a cantankerous God and a melancholic old man. God appears to lose the bet that creating humanity with freedom of choice would result in productive partnership. Humanity becomes, like in many of the Ancient Near East mythologies, a deformed creature worthy only of destruction. In many of these other stories God angrily starts again using new materials. It almost seems that he is doing the same in Genesis.

In the Noah tale, I see a different emphasis. Men have made a ruination of creation but God takes one man, one family and rebuilds humanity. God becomes a covenant carrier for Noah’s descendants. Noah found grace and was blessed — not for himself but for a new humanity. God promised to never again obliterate humanity utterly through a flood. Through covenant, God restored his original creation. This covenant was unconditional not based on what humanity did or does but upon who God is and will be. God stamps this covenant in the skies just to make it plain.

Since the tale is obviously written by a writer embedded in culture would it not be possible to read the story as suggesting that the retributive character of God depicted in a universal flood was not reflective of the Creator God. Perhaps the Deluge is a miswritten story needing correction? Not only does humanity need another chance but maybe our author is saying that people’s early conception of God’s relationship to humanity needs correction as well.

Imagine hearing this in the Exile. The people of Israel heard some of the more vicious prophets forecasting utter doom. “No longer my people!” they pronounced upon the nation. They were told that God had divorced his unfaithful bride. Just like the waves of the Deluge, Israel was swallowed by the Babylonian minions and left bereft of her traditions and access to God in a foreign land. The reiteration of the Noah story would have reminded them that God will preserve a remnant whom he will reestablish his covenant with. A covenant that will no longer depend on their own behavior but sheerly on God’s grace, a unilateral covenant whereby they will be given a new heart upon which the Torah will be written and obeyed naturally.

“I will pour out my spirit upon everyone; your sons and your daughters will prophesy, your old men will dream dreams, and your young men will see visions.”

The Noah story becomes for these Babylonian exiles and for us a perfect blend of judgment and redemption whereby they/we can see what they have done that resulted in the Deluge and also see what God has done to rescue them from it.

I read the story as an Exile as well. Like the people before the Deluge and after the Exile I am definitely post-catastrophic! I have a tendency toward autonomy, disobedience and selfishness just as they did. I also bear the consequences of my tendencies feeling cut off from God, myself and others. Nonetheless, I have hope because the Spirit has written a covenant on my heart, placed within me propensities toward discipleship and has forgiven me with a permeant seal, not only with a rainbow but also a cross that assures me of forgiveness and promises aliveness. Next time I feel like I am drowning in the waters of self exile I will have to remember these stories.

In chapter 2, a shadow creeps across this perfect picture as the serpent tempts them to mistrust. As they begin to investigate the fruit of the tree they are not to eat of, a seed of doubt is sown in their minds. Why are they not allowed to eat it? What will happen, really? Surely they won’t die?! The serpent suggests that their eyes will instead be opened and they’ll become like God. Gladding notes that instead of talking to God, they are now talking about God. Their unity is already experiencing a rift as they consider that something other than God could be good. Instead of being a creature, they began to grasp for the power of God.

As they exercised the freedom God had given them, they experienced catastrophe! They did not drop dead on the spot, but something died. They died as one being and were reborn as two, refusing to live in God’s world on God’s terms. Along with Adam and Eve, our exile begins here in life “east of Eden”, as the consequences of their sin impact all of creation.

Questions for Discussion

1) What am I capable of when I believe there isn’t enough?

2) How do you see the God of surprises in this story?

3) What kind of God image invites us to speak the truth?

4) How is talking about God different than talking to God?

5) What aspects of God emerge from the Noah story?

Scarcity

"The subtle serpent taps into our deepest anxiety as humans: the fear that what I have, no matter how good it may be, is not enough. The haunting suspicion that someone else has it better than me. That someone else is better than me. So, not only do I not have enough, I am not enough. I am less than." What are we capable of doing when we think we do not have enough? When we think we are not enough?

Bev Patterson: This morning Paul and Verda and I "pondered" this chapter and its legacy of tension and controversy that has been handed down through history. One thing that came up was how shame is so powerful in our lives and how it keeps us in hiding. For me, being "less than," fearing I’m inferior and don’t have what it takes unleashes a deep sense of that shame. What quickly follows is all manner of attitudes, actions, and reactions that have a defensive flavor.

In shame, I am capable of irrational judgement, mean-spiritedness, unhealthy competition, dark-hearted humour, deceit that translates into corrupt action and a desire to undermine my competition. If I were tribal, fully outfitted in the red-meme, I have no doubt I would resort to power-plays that would do physical damage.

But because I live in a more super-ego modality and have been brought up in an atmosphere of deceit when it comes to unsavory tendencies (i.e. anger which remains unconscious), I try to hide these power-plays behind niceties, covert manipulations and an attempt to look good through being dutiful. Outside of covenant with God, these niceties and attempts at being a "good girl" can be just as violent as being part of an ancient tribe who is at war.

These early stories, including the Cain & Abel/Tower of Babel stories are highly cautionary and instructive. They tell us we are still very much capable of murdering our brother/sister, having hubris to the point of competing with the gods and ultimately capable of choosing ego over a deeply loving and honest relationship with our creator. Shame keeps us from being honest and open with God and our human companions, creating a hollow space in us that craves filling.

We have rejected God as our true parent and turn away from the only thing that can fill that hollowness. Instead, we opt for knowledge without wisdom, judgement of reality based on our own instinctual controlling desires, elimination of those that get in the way of our satiation, and an Icarus-like drive that ignores all natural human limitation. Amazing that in light of the stark state of our souls, we, like Adam and Eve, get clothes to keep us warm, a path that offers a way back into relationship with God, each other and creation and a vocation, despite its toil and struggles. This mercy keeps us from becoming completely animal.

God of Surprises

God is a God of surprises. Our human disobedience is not met with divine displeasure. Instead, when what we do deserves death, God insists on life for us. How do you see this in the stories told in this chapter?

Paul Patterson: These Genesis stories are stories of restorative justice. God never blithely lets us off the hook nor does he utterly obliterate us for our disobedience. As Gladding brings to our attention, for every infraction there comes an empowerment, a comfort and invitation to restored fellowship. When we limit the Genesis stories to the literal or historic dimension we miss the narrative lessons contained in them.

What I take from the Adam and Eve story is that mistrust of God’s intentions and the refusal to accept a creaturely partnership with God leads to: scapegoating (i.e., Male/Female, Serpent/Human), deceitfulness, manipulation, shame and self-consciousness. I am called by the text to use these stories as narratives to form my values and virtues. They instruct me that when I mistrust, feel insecure, grasp equality and power then I am living in Adam not in the renewed humanity revealed in Christ the second Adam.

God has first declared his love for me. If I decide based on my own insecurity that God’s pledge of love is untrue and that I need to snatch power and autonomy from God (like Adam or the ancient Prometheus), I am not alive as I should be. I am living in the death-like domain of sinfulness. I constantly have to ask myself where I am getting my God image from... myself or the Shadow/Serpent? Or is it from my God a Creator/Father?

Because I am living this side of the great Catastrophe, my way home comes through attending this pattern, expecting it, working with it and not avoiding it. As Augustine says, the catastrophe is a happy fault (felix culpa) because it brings me to redemption and renewed fellowship, a condition I could never truly realize if I thought I was living a pre-catastrophic life. As shameful as it may feel to admit my creaturely arrogance, it is the only way to dignity and progressive growth, a genuinely free life.

Where Are You?

"Perhaps God asks ‘Where are you?’ not out of anger but in a gracious invitation to once more make ourselves vulnerable — before God, and before each other. Perhaps it is an invitation to speak the truth about our sin, an invitation to be found." What kind of God image does Gladding have as he asks this question? Does this image of God resonate with you? Why or why not?

Bev Patterson: Not sure if the question is "where are you" or "where were you"? “Where are you?” seems to carry the tone of concern, without the "wagging finger" whereas "Where were you?” sounds like us when we feel that indignant anger at being stood up and having our egos bruised.

I really liked this part of the chapter — discovering that God is not so much a punitive distant father as a parent who feels the suffering love of losing connection with the creatures he has so thoughtfully brought into being. "Where are you - I miss your company, I miss being in partnership with you, I miss tending creation with you, I miss the conversations that we have as we explore the image that is beginning to take root in you, I miss helping you with my wisdom and me learning what it means to become more human. Where are you - are you ok out there on your own? How is it working out for you? It's dangerous territory out there when you don't travel with love and guidance".

To be asked "where are you" is like God asking Adam and Eve "how goes it with your soul? (It can't be good if you feel you have to cover yourself and lie about the choices and mistakes you've made.)” The question "Where are you" has a discerning, incisive quality to it and it only feels threatening because we have chosen a life of deceit and autonomy. When we accept this question as loving, saving judgement, I think we can run back to God without the shame of question #1 and feel that restorative relief which comes when we are truly known — both in our sin and in our discipleship. "Where are you" in Gladding's perspective, is God waiting for us prodigals to make our way home again.

Talking About God

In what ways is the Cain and Abel tale another story that shows us the horrendous consequences of talking about God rather than to God?

Paul Patterson: The word that immediately comes to mind as I think about talking about God rather than to God is abstraction. Talking about God is for me to cobble together all the concepts that I have of God and attempt to place what I come up with within my intellectual grasp. Guess who just became God now? Where do I get these ideas anyway? I receive them from my culture, from my autonomous musing. And what do they serve but the advancement, security and flourishing of the same. I put the concept of God at the disposal of my interests. At the lowest conceptualization, I want God to be a fun-loving anarchist whose primary existence is dedicated to my comfort and interests. Within this concept I will always come off as a genuine seeker, a loving character, an authentic human being! I am the hero of my tale and God as the bumper sticker says is my co-pilot.

On the other hand, what if I invite God as he has revealed himself in Christ, scripture and community, into my life? What if I listen to God as he reveals himself, through God’s means of grace, which of course includes saving judgment, what then? Then I live prayerfully. I listen and express myself to the God who accompanies me as if we were alive together in a garden. He walks with me, his Spirit guides me, his Scriptures instruct me. I am open to the ways he consoles me and the ways he sometimes desolates me as needed. I can listen to my conscience, as it is Spirit controlled, and have at least the possibility of submitting or yielding to God’s words.

When I am in this place I am assuming God is actually alive, has an ontology apart from my autonomous constructs and my personal hero narratives. The assumption with this way of life, this way of continuous prayer, is that God is always present, always speaking, always willing to be related to (no matter what mood I am in) . The question then comes, as it did with our early Genesis ancestors, how will I use this freedom to walk with or away from the Creator? Will I conceptualize or will I pray?

Bev Patterson: “Talking about God rather than to God” — good distinction! The theological constructs and principles we create about God will not keep us from our sinful "murderous" ways if we are hell-bent on disobedience. In fact, having a well-crafted tower of ideas can keep us from the harshness of accepting responsibility for our motives and actions. Easier to be sneaky, hide behind intellectualism and play the blame-game if we have reduced God to an idea.

Talking to God, whether it is through "pondering Prayer" or through heart-felt conversation with the body of Christ, keeps us in that relational way which ultimately invites us to be more attentive to our God-given conscience. In relationships that are flesh and blood and when we are rooted in our covenant with the spirit of God/Christ, the stakes are raised as to the kinds of moral decisions we make.

Cal Wiebe: I like how Gladding deals with the Cain and Abel story. He suggests that God wants to give Cain a way out of committing the violence he has planned. God comes to Cain and gives him an encouragement and a warning. Do well and you'll remember you are accepted but beware sin is crouching at your tent flap to have its way with you. When Cain listened to a different voice than God's things got worse.

I think this is a very accurate story of things that actually happen. Last Friday at work, I had an opportunity to see it in operation. I was working up on a scaffold at the end of the day on a very difficult piece of trim. I was tired and impatient and just wanted to finish a frustrating piece of work. I clearly heard once or twice to take a little more time and measure things more accurately but I was fed up and said I'll just make it fit. Well, needless to say, not measuring did not help it fit any better and I left on Friday disappointed with a piece that I had to go back and fix. If I had listened to a saner voice I would have saved myself all sorts of aggravation. I thought of this incident while reading this chapter and realized that God was offering me a way out of frustration but because of my stubbornness I only made things worse for myself.

Connecting this incident to the Story made me realize just how true the story is to our human experience. Made me glad to be studying this book.

God’s First Covenant

The story of Noah and the flood is filled with powerful archetypal themes. Gladding touches on some of them with the following quotes: "The whole of creation groans with the harm humans have wrought upon it...And so God undid the work of creation...This is the first time in the Story that God's people are rescued from the sea...Yet God immediately began the process of re-creation…This promise to Noah is God's first covenant with humanity..." What aspects about God emerge from this story? Why does the old man (or scripture) choose to tell this story at this particular time?

Paul Patterson: It shouldn’t surprise us that modern interpreters of the Noah story see in it a cantankerous God and a melancholic old man. God appears to lose the bet that creating humanity with freedom of choice would result in productive partnership. Humanity becomes, like in many of the Ancient Near East mythologies, a deformed creature worthy only of destruction. In many of these other stories God angrily starts again using new materials. It almost seems that he is doing the same in Genesis.

In the Noah tale, I see a different emphasis. Men have made a ruination of creation but God takes one man, one family and rebuilds humanity. God becomes a covenant carrier for Noah’s descendants. Noah found grace and was blessed — not for himself but for a new humanity. God promised to never again obliterate humanity utterly through a flood. Through covenant, God restored his original creation. This covenant was unconditional not based on what humanity did or does but upon who God is and will be. God stamps this covenant in the skies just to make it plain.

Since the tale is obviously written by a writer embedded in culture would it not be possible to read the story as suggesting that the retributive character of God depicted in a universal flood was not reflective of the Creator God. Perhaps the Deluge is a miswritten story needing correction? Not only does humanity need another chance but maybe our author is saying that people’s early conception of God’s relationship to humanity needs correction as well.

Imagine hearing this in the Exile. The people of Israel heard some of the more vicious prophets forecasting utter doom. “No longer my people!” they pronounced upon the nation. They were told that God had divorced his unfaithful bride. Just like the waves of the Deluge, Israel was swallowed by the Babylonian minions and left bereft of her traditions and access to God in a foreign land. The reiteration of the Noah story would have reminded them that God will preserve a remnant whom he will reestablish his covenant with. A covenant that will no longer depend on their own behavior but sheerly on God’s grace, a unilateral covenant whereby they will be given a new heart upon which the Torah will be written and obeyed naturally.

“I will pour out my spirit upon everyone; your sons and your daughters will prophesy, your old men will dream dreams, and your young men will see visions.”

The Noah story becomes for these Babylonian exiles and for us a perfect blend of judgment and redemption whereby they/we can see what they have done that resulted in the Deluge and also see what God has done to rescue them from it.

I read the story as an Exile as well. Like the people before the Deluge and after the Exile I am definitely post-catastrophic! I have a tendency toward autonomy, disobedience and selfishness just as they did. I also bear the consequences of my tendencies feeling cut off from God, myself and others. Nonetheless, I have hope because the Spirit has written a covenant on my heart, placed within me propensities toward discipleship and has forgiven me with a permeant seal, not only with a rainbow but also a cross that assures me of forgiveness and promises aliveness. Next time I feel like I am drowning in the waters of self exile I will have to remember these stories.

blog comments powered by Disqus