Why Oppressed Communities Love Revelation - Week 9

22/05/16 14:30 Filed in: Literature of the Oppressed

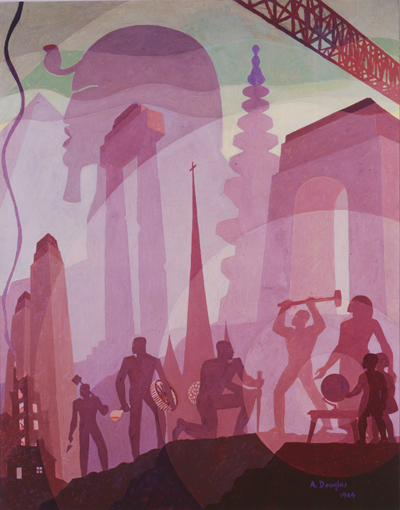

(Thanks to Jacob Lawrence for the above picture)

They say that more than any biblical book, Revelation speaks to marginalized and powerless people, to anyone familiar with struggle. Scholars call it the literature of the oppressed. It was originally written for those whom South African theologian Allan Boesak calls “God’s little people” — communities of people who struggled (and continue to struggle) under oppression.

And oppression can take many forms. Some from Revelation’s original audience were openly persecuted for their faith but others lost their spiritual integrity with the constant, subtle pressure to conform. Still others were so seduced by empire that they became complacent and their faith lost its edge. Imagine Revelation as a message from the underside, speaking to oppressed people of every kind, written to comfort beleaguered churches struggling under Roman imperial violence and power.

People going through tough times are often remarkably resilient. There’s something within them that keeps them hoping for life to get better, even when darkness seems to be winning. True hope is not a wimpy word. It’s what preacher Peter Gomes calls a muscular hope, the stuff that gets us through and beyond when the worst that can happen happens. “Hope is forged on the anvil of adversity,” he famously said.

The original audience of Revelation would have understood that. Revelation portrays the worst of the world’s violence and yet the power of a slaughtered Lamb is shown to be more powerful. What could be more hopeful?

Revelation has continued to speak beyond the first century to oppressed people throughout history. I would guess that anyone battling demons of any kind, whether in the outside world or within the heart, would find the images evocative. They picture not only the utter darkness that cloaks the earth, but also the glory and hope of God which is ultimately stronger. As profoundly dark as this universe can be, the Story says it has been and will be restored to God’s intention.

Almost all the speeches from Martin Luther King Jr contain the kind of hope that grabs us through the darkness and pulls us into light. He told the people that someday they’d be able to say, “Free at last, free at last, thank God almighty, we’re free at last.” While those exact words from his famous “I have a dream” speech don’t contain words from Revelation, many other speeches do. They draw on hope from the next world as the source of encouragement for life in this world. He gives people the sense that amid oppression, the future is ultimately open, not closed, and that despite appearances to the contrary, they don’t have to remain captive to the present.

King’s speeches were written when slavery was a recent memory. In the same way, it’s probably no accident that John wrote Revelation when the memory of the terrible Jewish War of 68-70 AD was fresh on everyone’s mind. The author himself could have been a refugee from that war just 20 years earlier. Those early readers would have been struggling with the invisible scars of war affected people everywhere — flashbacks, disturbing dreams, memories of carnage and loss. They would have identified with the violent images in Revelation. As they kept turning the page, other images of the Lamb and the city of New Jerusalem gave hope that they were not ultimately captive to the darkness. And they would have identified with the Lamb who understands their suffering.

Everyone familiar with darkness needs to see behind the curtain. John’s goal was to help people see and unveil the truth about the world behind all the violence. The visions pulled back the curtain to expose Rome’s brutal power, and then offered a way of seeing God’s vision of hope for the world. This was the alternative to Rome’s violence and power.

Revelation also played a vital role in the African American slave culture. Scenes of the New Jerusalem caught the imagination of those who were enslaved and gave them impetus to work for social change despite the seeming prison they were in. “Negro spirituals," the music of the slave culture, spoke about the singer’s hope for deliverance from oppression, for freedom and a better life.

Anyone who grew up in church probably remembers singing songs about heaven. “This world is not my home, I’m just a-passing through…” Those kind of songs can make a person impatient! “Pie in the sky when you die” may be all right for some, but where is God’s kingdom now? Singing about a “heavenly hope” and for freedom in the next life could be seen as fostering a sense of acceptance of the status quo. A cynic might say that their dose of heavenly hope merely helped them put up with their bond in the here and now, but not change it. Was it right to for the slaves to sing about the next world when the present one was deeply unfair? Did it teach them to stay in their place and not look for anything better in this life?

If you take a closer look at the culture, however, you can see how the hope for a better life in the next world seeped into the present. The spiritual resistance within the songs began to inspire social change. The sense that things can be different in God’s future can foster a spirit that resists being captive by the present. That kind of resistance can lead to change. Revelation changed the image of the future for the black slaves, reinforcing the sense that the “way things were” didn’t have to be the final word.

The life of a woman named Sojourner Truth demonstrated how heavenly hopes of a better tomorrow could lead to social change today. One of the most famous African American women of the 19th century, she worked for women’s rights and for the abolition of slavery. Like most slaves of her day, she received beatings that scarred her forever, but in 1827 she had a spiritual experience which led her to a Methodist church. There she learned a hymn about the New Jerusalem which would become her favorite. The hymn contained two contrasting realities — the vision of the heavenly city filled with light, and the reality of human suffering. Those two realities are Revelation in a nutshell, and by putting them together, the singer knew that suffering did not have to be the final word. Oppression did not have to define the future. There is something more to hope for. The little people, those people at the bottom, would someday wear white robes and this gave them reason to persevere in the present.

It was at exactly this time in her life that Sojourner Truth began to make legal history. She was the first woman to win a case against a white man in court. He had sold her son illegally and she was able to free him from slavery. This story is amazing because she was successful against so many odds. She went on to become a traveling preacher, an early women’s rights advocate and eventually met with President Lincoln. She compelled black people to fight for their own freedom and continued to lead social reform.

It’s been noted that Revelation may have seemed more at home in the world of slaves than in the white churches. The spiritual visions of Revelation might have seemed outrageous to the comfortable white slave owners, but to the slave, they were a source of religious authority and inspiration. Revelation fit in their world view. Singing about its images helped them move from future hope to present realities with ease. When listening and watching the inspired singing, a person would wonder, were the slaves singing about a better world in heaven or a better world on earth? The answer is both.

It’s interesting that the authorities noticed this connection too. The other-worldly imagery could seem dangerously close to life in the here and now. A song called “My Father, how long?” had been sung for many years in the slave community. It referred to the oppressed in Revelation, who are grievously moaning under God’s throne about how long they would still be suffering. On the one hand, it was an innocent song, but the powers that be began to hear it as subversive. One line of the song said, “We will soon be free,” and authorities were not sure, were they singing of the after-life or an uprising about to happen? The line between future and present seemed to blur. Sure, they had hope for the next world, but as soon as the war began to break out, it gave them incentive to bring change now. At the beginning of the American civil war, some people were even put in jail for singing it!

The slaves and civil rights activists who received hope from Revelation proved that a person can suffer deeply yet remain patiently hopeful. They showed us that the future is open and that we can live a little differently than we are now because something will break in and change. The slaves had a community that was like the Kingdom of God. Their love for one another, their support of one another, their rituals, singing and protesting — all that was the community in the midst of suffering. Even though some died, they lived in such a way that their life was noticeable. They proved that you can have muscular hope when circumstances look anything but hopeful. The early civil rights movement was religious in nature, and much of the impetus for change came from the book of Revelation.

Does God’s future seep into current reality? Does the hope of New Jerusalem speak to child prostitutes in Asia? To former refugees in a new land, hoping for a new start but meeting up with prejudice and intolerance? Does the book inspire hopeful long-suffering or violent revolution? Either could be true, but their faithfulness and endurance witnesses to the Lamb just like the martyrs under the throne. Their suffering is very much like the suffering of Jesus and the slain-but-risen lamb attests that there is much power in that weakness.

So often in today’s world, there’s more anger and a hunger for vengeance. It’s time once again to be defined not by the past but by God’s future.

Post script — On the evening that Watershed discussed this lecture by Craig Koester, someone brought a quote from a book about Ephesians. It fit so perfectly with this theme that it seemed like a perfect ending here as well.

“As part of the transformed people of God, I am no longer defined by my past, the things I have done and the things that have been done to me. I am no longer defined by where I am from or what people have said about me, the labels they have used to speak of me and the ways I have been pigeon-holed. I have a new history, one that stretches back to God’s design for redemption and God’s pursuit of God’s good world to save it.

"Because of our new history, painful things that have been done to me are now swallowed up in my renewed history and reconfigured. They must now be re-remembered in the light of all that God has done and is doing. The gospel speaks to our painful pasts and says that they can change. In fact, the past is always changing in light of the story that God is unfolding in time and the story into which God is always in folding my life."

From: The Drama of Ephesians by Timothy Zombis

Next Post

They say that more than any biblical book, Revelation speaks to marginalized and powerless people, to anyone familiar with struggle. Scholars call it the literature of the oppressed. It was originally written for those whom South African theologian Allan Boesak calls “God’s little people” — communities of people who struggled (and continue to struggle) under oppression.

And oppression can take many forms. Some from Revelation’s original audience were openly persecuted for their faith but others lost their spiritual integrity with the constant, subtle pressure to conform. Still others were so seduced by empire that they became complacent and their faith lost its edge. Imagine Revelation as a message from the underside, speaking to oppressed people of every kind, written to comfort beleaguered churches struggling under Roman imperial violence and power.

People going through tough times are often remarkably resilient. There’s something within them that keeps them hoping for life to get better, even when darkness seems to be winning. True hope is not a wimpy word. It’s what preacher Peter Gomes calls a muscular hope, the stuff that gets us through and beyond when the worst that can happen happens. “Hope is forged on the anvil of adversity,” he famously said.

The original audience of Revelation would have understood that. Revelation portrays the worst of the world’s violence and yet the power of a slaughtered Lamb is shown to be more powerful. What could be more hopeful?

Revelation has continued to speak beyond the first century to oppressed people throughout history. I would guess that anyone battling demons of any kind, whether in the outside world or within the heart, would find the images evocative. They picture not only the utter darkness that cloaks the earth, but also the glory and hope of God which is ultimately stronger. As profoundly dark as this universe can be, the Story says it has been and will be restored to God’s intention.

Almost all the speeches from Martin Luther King Jr contain the kind of hope that grabs us through the darkness and pulls us into light. He told the people that someday they’d be able to say, “Free at last, free at last, thank God almighty, we’re free at last.” While those exact words from his famous “I have a dream” speech don’t contain words from Revelation, many other speeches do. They draw on hope from the next world as the source of encouragement for life in this world. He gives people the sense that amid oppression, the future is ultimately open, not closed, and that despite appearances to the contrary, they don’t have to remain captive to the present.

King’s speeches were written when slavery was a recent memory. In the same way, it’s probably no accident that John wrote Revelation when the memory of the terrible Jewish War of 68-70 AD was fresh on everyone’s mind. The author himself could have been a refugee from that war just 20 years earlier. Those early readers would have been struggling with the invisible scars of war affected people everywhere — flashbacks, disturbing dreams, memories of carnage and loss. They would have identified with the violent images in Revelation. As they kept turning the page, other images of the Lamb and the city of New Jerusalem gave hope that they were not ultimately captive to the darkness. And they would have identified with the Lamb who understands their suffering.

Everyone familiar with darkness needs to see behind the curtain. John’s goal was to help people see and unveil the truth about the world behind all the violence. The visions pulled back the curtain to expose Rome’s brutal power, and then offered a way of seeing God’s vision of hope for the world. This was the alternative to Rome’s violence and power.

African American Slave Culture

Revelation also played a vital role in the African American slave culture. Scenes of the New Jerusalem caught the imagination of those who were enslaved and gave them impetus to work for social change despite the seeming prison they were in. “Negro spirituals," the music of the slave culture, spoke about the singer’s hope for deliverance from oppression, for freedom and a better life.

Anyone who grew up in church probably remembers singing songs about heaven. “This world is not my home, I’m just a-passing through…” Those kind of songs can make a person impatient! “Pie in the sky when you die” may be all right for some, but where is God’s kingdom now? Singing about a “heavenly hope” and for freedom in the next life could be seen as fostering a sense of acceptance of the status quo. A cynic might say that their dose of heavenly hope merely helped them put up with their bond in the here and now, but not change it. Was it right to for the slaves to sing about the next world when the present one was deeply unfair? Did it teach them to stay in their place and not look for anything better in this life?

If you take a closer look at the culture, however, you can see how the hope for a better life in the next world seeped into the present. The spiritual resistance within the songs began to inspire social change. The sense that things can be different in God’s future can foster a spirit that resists being captive by the present. That kind of resistance can lead to change. Revelation changed the image of the future for the black slaves, reinforcing the sense that the “way things were” didn’t have to be the final word.

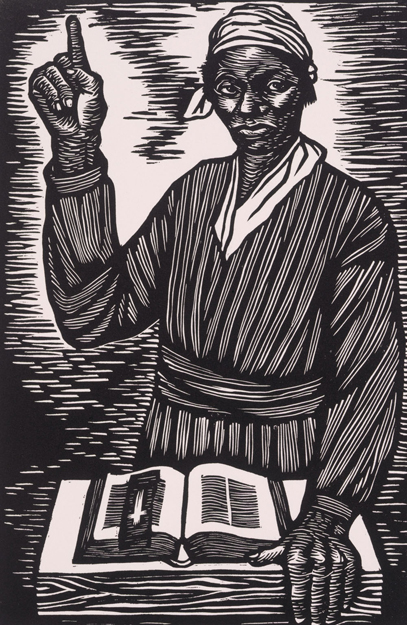

Sojourner Truth

The life of a woman named Sojourner Truth demonstrated how heavenly hopes of a better tomorrow could lead to social change today. One of the most famous African American women of the 19th century, she worked for women’s rights and for the abolition of slavery. Like most slaves of her day, she received beatings that scarred her forever, but in 1827 she had a spiritual experience which led her to a Methodist church. There she learned a hymn about the New Jerusalem which would become her favorite. The hymn contained two contrasting realities — the vision of the heavenly city filled with light, and the reality of human suffering. Those two realities are Revelation in a nutshell, and by putting them together, the singer knew that suffering did not have to be the final word. Oppression did not have to define the future. There is something more to hope for. The little people, those people at the bottom, would someday wear white robes and this gave them reason to persevere in the present.

It was at exactly this time in her life that Sojourner Truth began to make legal history. She was the first woman to win a case against a white man in court. He had sold her son illegally and she was able to free him from slavery. This story is amazing because she was successful against so many odds. She went on to become a traveling preacher, an early women’s rights advocate and eventually met with President Lincoln. She compelled black people to fight for their own freedom and continued to lead social reform.

It’s been noted that Revelation may have seemed more at home in the world of slaves than in the white churches. The spiritual visions of Revelation might have seemed outrageous to the comfortable white slave owners, but to the slave, they were a source of religious authority and inspiration. Revelation fit in their world view. Singing about its images helped them move from future hope to present realities with ease. When listening and watching the inspired singing, a person would wonder, were the slaves singing about a better world in heaven or a better world on earth? The answer is both.

It’s interesting that the authorities noticed this connection too. The other-worldly imagery could seem dangerously close to life in the here and now. A song called “My Father, how long?” had been sung for many years in the slave community. It referred to the oppressed in Revelation, who are grievously moaning under God’s throne about how long they would still be suffering. On the one hand, it was an innocent song, but the powers that be began to hear it as subversive. One line of the song said, “We will soon be free,” and authorities were not sure, were they singing of the after-life or an uprising about to happen? The line between future and present seemed to blur. Sure, they had hope for the next world, but as soon as the war began to break out, it gave them incentive to bring change now. At the beginning of the American civil war, some people were even put in jail for singing it!

Defined by God’s Future

The slaves and civil rights activists who received hope from Revelation proved that a person can suffer deeply yet remain patiently hopeful. They showed us that the future is open and that we can live a little differently than we are now because something will break in and change. The slaves had a community that was like the Kingdom of God. Their love for one another, their support of one another, their rituals, singing and protesting — all that was the community in the midst of suffering. Even though some died, they lived in such a way that their life was noticeable. They proved that you can have muscular hope when circumstances look anything but hopeful. The early civil rights movement was religious in nature, and much of the impetus for change came from the book of Revelation.

Does God’s future seep into current reality? Does the hope of New Jerusalem speak to child prostitutes in Asia? To former refugees in a new land, hoping for a new start but meeting up with prejudice and intolerance? Does the book inspire hopeful long-suffering or violent revolution? Either could be true, but their faithfulness and endurance witnesses to the Lamb just like the martyrs under the throne. Their suffering is very much like the suffering of Jesus and the slain-but-risen lamb attests that there is much power in that weakness.

So often in today’s world, there’s more anger and a hunger for vengeance. It’s time once again to be defined not by the past but by God’s future.

Post script — On the evening that Watershed discussed this lecture by Craig Koester, someone brought a quote from a book about Ephesians. It fit so perfectly with this theme that it seemed like a perfect ending here as well.

“As part of the transformed people of God, I am no longer defined by my past, the things I have done and the things that have been done to me. I am no longer defined by where I am from or what people have said about me, the labels they have used to speak of me and the ways I have been pigeon-holed. I have a new history, one that stretches back to God’s design for redemption and God’s pursuit of God’s good world to save it.

"Because of our new history, painful things that have been done to me are now swallowed up in my renewed history and reconfigured. They must now be re-remembered in the light of all that God has done and is doing. The gospel speaks to our painful pasts and says that they can change. In fact, the past is always changing in light of the story that God is unfolding in time and the story into which God is always in folding my life."

From: The Drama of Ephesians by Timothy Zombis

Questions for Engagement — Week 9

- Do you know any songs based on themes or images from Revelation?

- Images of New Jerusalem had an important place in African American music. How might such images have encouraged a sense of acceptance of current conditions? How might such images have encouraged active efforts for social change, as in the case of Sojourner Truth?

- Has a better vision for the future ever helped you hang on to hope or seek change now? Has a song ever changed your outlook?

- Christians always live in a tension between the “already” and the “not yet.” How does this tension live in Revelation, and how does it play out in our everyday life?

- Revelation invites believers to live along the river of life, sharing the healing and peace of the tree of life. What does this vision say to you?

- What gives you hope amid suffering?

In case you’d like to read more…

- The Great Courses, “Revelation in African American Culture”, Lecture 20

- Barbara Rossing’s 5 minute video called “Singing Hymns of Hope” relates to this week’s theme as well.

- And by the way, if you’d like to learn more about Barbara Rossing and how she got into studying Revelation, watch this 2 minute video.

- To learn more about Peter Gomes, check out this link

- To hear Peter Gomes’ 2009 sermon called “The Power of Hope”, check out sermon #23 at this link

- For a short biography and video on Sojourner Truth, see this link

Next Post

blog comments powered by Disqus